List of Works

Download the work list. (PDF/965KB)

Structure of the Exhibition

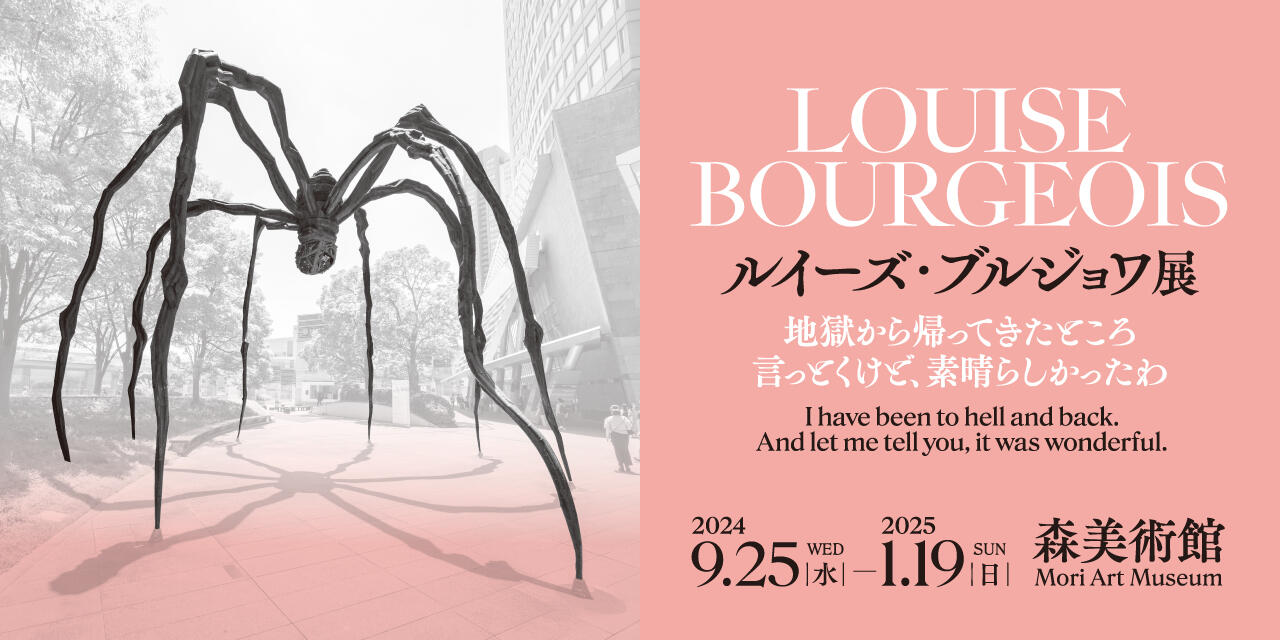

The exhibition consists of three chapters based on Bourgeois’s relationships with her family, a prime source of her inspiration. Chapter 1, “Do Not Abandon Me,” is about her relationship with her mother; Chapter 2, “I Have Been to Hell and Back,” is based on the negative emotions towards her father; and Chapter 3, “Repairs in the Sky,” is about the restoration of broken relationships and emotional liberation.

In addition, two smaller spaces between the chapters, referred to as Columns, present a chronological view of important early works.

Chapter 1: Do Not Abandon Me

Bourgeois suffered from a lifelong fear of abandonment. The first chapter of the exhibition, “Do Not Abandon Me,” traces this fear back to the original separation from the mother. Bourgeois explored the theme of motherhood in all its ambivalence and complexity, as demonstrated in her sculpture Nature Study. She believed that the mother-child relationship set the template for all future relationships.

Bourgeois once said that her sculpture was her body, and her body was her sculpture. Images of bodily fragments often appear in her work as symbols and symptoms of psychic instability and disintegration.

The Good Mother (detail)

2003

Fabric, thread, and stainless steel

Sculpture and stand: 109.2 x 45.7 x 38.1 cm

Photo: Christopher Burke

© The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR, Tokyo, and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Nature Study

1984

Rubber and stainless steel

Sculpture: 76.2 x 48.3 x 38.1 cm

Photo: Christopher Burke

© The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR, Tokyo, and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Chapter 2: I Have Been to Hell and Back

The works in the second chapter, “I Have Been to Hell and Back,” bear witness to a host of conflictual and negative emotions: anxiety, guilt, jealousy, suicidal impulses, murderous hostility, fear of intimacy and dependency, and fear of rejection. The fabric bust Rejection is such an example.

Bourgeois believed that making sculpture was a form of exorcism - a way of discharging unwelcome or unmanageable emotions. Working against the resistance of the material provided her with an outlet for her aggression.

Through her analysis, Bourgeois came to understand that much of her work was generated as a negative reaction against her father. In 1974, Bourgeois created the installation The Destruction of the Father, which stages a fantasy of cannibalistic revenge against a domineering father figure. This seminal piece represents the culmination, and in many ways the synthesis, of the forms and materials she had explored throughout the 1960s and early 1970s – from undulating abstract landscapes to more sexually explicit body parts.

Rejection

2001

Fabric, steel, wood, lead, aluminum, and glass

Sculpture: 63.5 x 33 x 30.5 cm

Photo: Christopher Burke

© The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR, Tokyo, and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Destruction of the Father

1974

Archival polyurethane resin, wood, fabric, and light

237.8 x 362.3 x 248.6 cm

Collection: Glenstone Museum, Potomac, MD, USA

Photo: Ron Amstutz

© The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR, Tokyo, and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Chapter 3: Repairs in the Sky

Bourgeois saw herself as a survivor, and her art as the instrument that enabled her survival, like a crutch or prosthesis. The final chapter of the exhibition, “Repairs in the Sky,” shows how her art enabled her to bring conscious and unconscious, maternal and paternal, past and present into a precarious balance. Topiary IV and Clouds and Caverns beautifully exemplify such restorative and regenerative forces. As Bourgeois famously stated, “art is a guaranty of sanity.”

Bourgeois believed that the artist enjoyed unusually direct access to the unconscious and possessed the gift of sublimation – that is, the ability to channel sexual and aggressive drives and impulses toward artistic ends. Her sculptures and other works are symbolic representations of psychological states, and constitute an attempt to impose order on the chaos of her emotions.

By using clothing and other fabrics from her life, Bourgeois acted out the wish to hold on to the past and give it permanent form in her art. Sewing and joining were symbolic actions that ward off the fear of separation and abandonment. They also evince an unconscious identification with her mother, who ran the family’s tapestry restoration workshop in the Parisian suburbs.

Topiary IV

1999

Steel, fabric, beads, and wood

68.6 x 53.3 x 43.2 cm

Photo: Christopher Burke

© The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR, Tokyo, and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Clouds and Caverns

1982-1989

Metal and wood

274.3 x 553.7 x 182.9 cm

Photo: Christopher Burke

© The Easton Foundation/Licensed by JASPAR, Tokyo, and VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

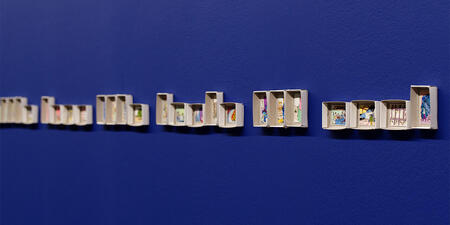

Column 1: Fallen Woman - Early Paintings and Sculptures

Column 1 focuses on paintings and sculptures Bourgeois created during her first decade in New York. She moved to the city from Paris in 1938 after marrying the American art historian Robert Goldwater. The motifs in her paintings, which feature self-portraits and renderings of buildings, trees, and female figures, recurred in her work over the subsequent 60 years. The paintings have earned increased attention in recent years as a singular body of work.

Among the works in column 1 are a painting from Bourgeois’s “Femme Maison” series (1946-1947) and sculptures from her “Personage” series (1946-1954). The “Femme Maison” paintings depict amalgams of architectural structures and female figures, and the anthropomorphic “Personages” evoke family members and friends that Bourgeois left behind in France.

Column 2: Unconscious Landscape - Sculptures of the 1960s

On display in column 2 are works from the 1960s, made as Bourgeois gradually emerged from the creative hiatus that accompanied her focus on psychoanalysis after her father’s death and resumed producing art in earnest.

In the early 1960s, the verticality of the carved wood “Personages” from the 1940s gave way to horizontality and interiority. Bourgeois began molding and pouring softer materials, such as resin, plaster, and latex, and her depictions of the human form became increasingly abstract. For example, den-like and nest-like works such as Lair (1962) evoke both the protective and confining nature of shelter. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Bourgeois’s marble and bronze sculptures and drawings again start to show a repetition of forms, which stretch upward and evoke the body or landscape.